John W. Hopper

was in the Indiana 79th Infantry (Union)

His son,

Frank M. Hopper

was in the Kentucky 4th Infantry

(Confederate)

John was wounded in this battle (musket ball lodged under his rib) and sent to Nashville to recover.

Family lore does not reveal that either was aware that they faced each other in this fateful battle.

The Battle of Stones River

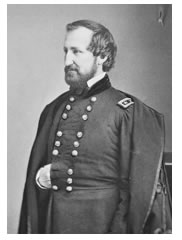

Major General William S. Rosecrans

Why Stones River?

As 1862 drew to a close, President Abraham Lincoln was desperate for a military victory. His armies were stalled, and the terrible defeat at Fredericksburg spread a pall of defeat across the nation. There was also the Emancipation Proclamation to consider. The nation needed a victory to bolster morale and support the proclamation when it went into effect on January 1, 1863.

The Confederate Army of Tennessee was camped in Murfreesboro, Tennessee only 30 miles away from General William S. Rosecrans’ army in Nashville. General Braxton Bragg chose this area in order to position himself to stop any Union advances towards Chattanooga and to protect the rich farms of Middle Tennessee that were feeding his men.

Union General-In-Chief Henry Halleck telegraphed Rosecrans telling him that, “… the Government demands action, and if you cannot respond to that demand some one else will be tried.”

On December 26, 1862, the Union Army of the Cumberland left Nashville to meet the Confederates. This was the beginning of the Stones River Campaign.

The Union Approach

On December 26, 1862, the Union Army of the Cumberland left Nashville to engage Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. General William S. Rosecrans sent the three wings of his army on different routes in search of the Rebel army.

Rain, sleet and fog combined with spirited resistance from Confederate cavalry slowed the Federal advance. By the evening of December 30, 1862 both armies faced each other in the fields and forests west and south of Murfreesboro.

During the night, Bragg and Rosecrans planned their attacks. Both chose to attack the right flank of the enemy and cut off their supply line and escape route. Bragg extended his lines to the south using all but General John C. Breckinridge’s Division of General William Hardee’s Corps. This movement of troops left only Breckinridge’s men to face Rosecrans’s planned onslaught on the east bank of the Stones River with General Thomas J. Crittenden’s Left Wing.

While the generals planned, the men lay down in the mud and rocks trying to get some sleep. The bands of both armies played tunes to raise the men’s spirits. It was during this " battle of the bands " that one of the most poignant moments of the war occurred. Sam Seay of the First Tennessee Infantry described what happened that evening.

“Just before ‘tattoo’ the military bands on each side began their evening music. The still winter night carried their strains to great distance. At every pause on our side, far away could be heard the military bands of the other. Finally one of them struck up ‘Home Sweet Home.’ As if by common consent, all other airs ceased, and the bands of both armies as far as the ear could reach, joined in the refrain. Who knows how many hearts were bold next day by reason of that air?”

Turning the Union Right

At dawn on December 31, 1862, General J. P. McCown’s Division with General Patrick Cleburne’s men in support stormed across the frosted fields to attack the Federal right flank. Their plan was to swing around the Union line in a right wheel and drive their enemy back to the Stones River while cutting off their main supply routes at the Nashville Pike and the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad.

The men of General Richard Johnson’s Division were cooking their meager breakfasts when the sudden crackle of the pickets’ fire raised the alarm. The Confederate tide swept regiment after regiment from the field.

Lieutenant Tunnel of the Fourteenth Texas Infantry described the confusion.

“Many of the Yanks were either killed or retreated in their nightclothes … We found a caisson with the horses still attached lodged against a tree and other evidences of their confusion. The Yanks tried to make a stand whenever they could find shelter of any kind. All along our route we captured prisoners, who would take refuge behind houses, fences, logs, cedar bushes and in ravines.”

Union artillery tried to hold its ground, but the butternut and gray wave swept over them. Federal commanders tried to halt and resist at every fence and tree line, but the Confederate attack was too powerful to stop against such a piecemeal defense.

Soon General Jefferson C. Davis's Division found itself caught between attacks from the front and the right. By 8:30 AM those units also began to fray and retreat to the north.

The ground itself helped stave off disaster. The rocky ground and cedar forests blunted the Confederate assault, and Rebel units began to come apart. Confederate artillery struggled to keep pace with the infantry. Still, the Army of the Cumberland’s right flank was shattered beyond repair.

The Slaughter Pen

After McCown’s dawn assault, Confederate units to the north began attacking the enemy in their front. These attacks were not meant to break through, but to hold Union units in place as the flanking attack swept up behind them.

General Philip Sheridan had his men rise early and form a line of battle. His men were able to repulse the first enemy attack, but the loss of the divisions to his right forced Sheridan’s commanders to reposition their lines to keep Cleburne’s Division from cutting off their escape route. Sheridan’s lines pivoted to the north, anchored by General James Negley’s Division in the trees and rocks along McFadden Lane.

Confederate brigades assaulted Sheridan’s and Negley’s Divisions without coordination. The terrain made communication and cooperation between units nearly impossible. For more than two hours, the Union forces fell back step by bloody step slowing the Confederate assault.

By noon, the Confederate Brigades of A.P. Stewart, J. Patton Anderson, George Maney, A.M. Manigault, and A.J. Vaughn assaulted the Union salient from three sides. With their ammunition nearly spent, Negley’s and Sheridan’s lines shattered and their men made their way north and west through the cedars towards the Nashville Pike.

The cost of this delaying action was enormous. Sam Watkins of the First Tennessee Infantry, CS was amazed at the bloodshed.

“I cannot remember now of ever seeing more dead men and horses and captured cannon all jumbled together, than that scene of blood and carnage … on the (Wilkinson) … Turnpike; the ground was literally covered with blue coats dead.”

All three of Sheridan’s brigade commanders were killed or mortally wounded and many Federal units lost more than one-third of their men. Many Confederate units fared little better. Union soldiers recalled the carnage as looking like the slaughter pens in the stockyards of Chicago. The name stuck.

Defending the Nashville Pike

While the fighting raged in the Slaughter Pen, General Rosecrans was busy trying to save his army. He cancelled the attack across the river and funneled his reserve troops into the fight hoping to stem the bleeding on his right. Rosecrans and General George Thomas rallied fleeing troops as they approached the Nashville Pike and a new line began to form along that vital lifeline backed up by massed artillery.

The new horseshoe shaped line gave the Army of the Cumberland solid interior lines and better communication than their attackers. The Union cannon covered the long open fields between the cedars and the road. Most of the troops in this line had full cartridge boxes and knew that they must hold here or the battle would be lost.

Again the woods and rocky ground helped the Union. Confederate organization fell apart as they struggled through the cedars. Most of Confederate artillery was unable to penetrate the dense forests strewn with limestone outcroppings. Each wave of enemy attack along the pike was repulsed in bloody fashion by the Federal artillery that commanded the field.

Lietenant Alfred Pirtle (Ordnance Officer, Rousseau’s Division) watched the cannon do their deadly work that afternnon.

“… then our batteries opened on them with a deafening unceasing fire, throwing twenty-four pounds of iron from each piece, across that small space. … But men were not born who could longer face that storm of canister. … They broke, they fled, and some took refuge in the clump of trees and weeds.”

As night approached, the Union army was bloody and battered, but it retained control of the pike and its vital lifeline to Nashville. Although Confederate cavalry would wreak havoc on Union wagon trains, enough supplies got through to give General Rosecrans the option to continue the fight.

Hell's Half Acre

The Round Forest was a crucial position for the Army of the Cumberland. Poised between the Nashville Pike and the Stones River, the forest anchored the left of the Union line. Colonel William B. Hazen’s Brigade was assigned this crucial sector.

At 10 AM, General James Chalmers’ Mississippians advanced across the fields in front of Hazen’s men. The partially burned Cowan house forced Chalmers’ men to split just before they came a within range of the Union muskets. Artillery batteries guarded Hazen’s flanks with deadly fire while the infantry poured volley after volley into the Confederate ranks. General Chalmers was wounded as his men wavered then broke.

Chalmers’ attack was followed by General Daniel Donelson’s Brigade as General Bragg sought to tie up Rosecrans’ reserves pressing the Union left. Donelson’s men crashed through Cruft’s Brigade south of the pike. Hazen’s men held firm to the north and Union reinforcements were able to seal the breach.

During the afternoon of December 31st, Bragg called on General Breckinridge’s troops to hammer the anchor point of the Union line guarding the Nashville Pike. Two brigades went in first suffering the same fate as those that went before. Two more of Breckinridge’s Brigades made a final assault as daylight began to fail. Hazen’s men, reinforced now by Harker’s Brigade, clung to their positions.

The carnage as described by J. Morgan Smith of the Thirty-second Alabama Infantry prompted soldiers to name the field Hell’s Half Acre.

“We charged in fifty yards of them and had not the timely order of retreat been given — none of us would now be left to tell the tale. … Our regiment carries two hundred and eighty into action and came out with fifty eight.”

Colonel Hazen’s Brigade was the only Union unit not to retreat on the 31st. Their stand against four Confederate attacks gave Rosecrans a solid anchor for his Nashville Pike line that finally stopped the Confederate tide.

Hazen’s men were so proud of their efforts in this area that they erected a monument there after the battle. The Hazen Brigade Monument is the oldest intact Civil War monument in the nation.

Breckinridge's Charge

After spending January 1, 1863 reorganizing and caring for the wounded, the two armies came to blows again on the afternoon of January 2nd. General Bragg ordered Breckinridge to attack General Horatio Van Cleve’s Division (commanded by Colonel Samuel Beatty) occupying a hill overlooking McFadden’s Ford on the east side of the river.

Breckinridge reluctantly launched the attack with all five of his brigades at 4 PM. The Confederate charge quickly took the hill and continued on pushing towards the ford. As the Confederates attacked, they came within range of fifty-seven Union cannon massed on the west side of the Stones River. General Crittenden watched as his guns went to work.

“Van Cleve’s Division of my command was retiring down the opposite slope, before overwhelming numbers of the enemy, when the guns … opened upon the swarming enemy. The very forest seemed to fall … and not a Confederate reached the river.”

The cannon took a heavy toll. In forty-five minutes their concentrated fire killed or wounded more than 1,800 Confederates. A Union counterattack pushed the shattered remnants of Breckinridge’s Division back to Wayne’s Hill.

Faced with this disaster and the approach of Union reinforcements, General Bragg ordered the Army of Tennessee to retreat on January 3, 1863. Two days later, the battered Union army marched into Murfreesboro and declared victory.

" A Hard Earned Victory "

The Battle of Stones River was one of the bloodiest of the war. More than 3,000 men lay dead on the field. Nearly 16,000 more were wounded. Some of these men spent as much as seven agonizing days on the battlefield before help could reach them. The two armies sustained nearly 24,000 casualties, which was almost one-third of the 81,000 men engaged.

As the Army of Tennessee retreated they gave up a large chunk of Middle Tennessee. The rich farmland meant to feed the Confederates now supplied the Federals. General Rosecrans set his army and thousands of contraband slaves to constructing a massive fortification, Fortress Rosecrans that served as a supply depot and base of occupation for the Union for the duration of the war.

President Lincoln got the victory he wanted to boost morale and support the Emancipation Proclamation. How important was this victory to the Union? Lincoln himself said it best in a telegram to Rosecrans later in 1863.

“I can never forget, if I remember anything, that at the end of last year and the beginning of this, you gave us a hard earned victory, which had there been a defeat instead, the country scarcely could have lived over.”